Getting out the urushi.

I have to admit I was a little nervous about actually beginning to work with urushi again. In fact I could be considered almost obsessive about not getting a rash. My first experience with urushiol was not associated with Asian lacquer but as a teenager on a beach. I was walking with a boy I knew along the edge of Wasaga beach, 14 kilometer stretch of white sand, famous for being the takeoff point for Canada’s first flight over the Atlantic. A lesser-known fact about the beach is that it provides ideal growing conditions for poison ivy, an urushiol producing plant related to Toxicodendron Vernicifluum. After walking a short stretch I recognized the ‘leaves of three let it be’ plant. The boy disagreed and to prove a point picked me up and dumped me in it. You can guess who was right. Since I was wearing short shorts and a halter-top I got a massive rash with weeping blisters on my legs and a lumpy rash on my back. It took three weeks of misery to heal.

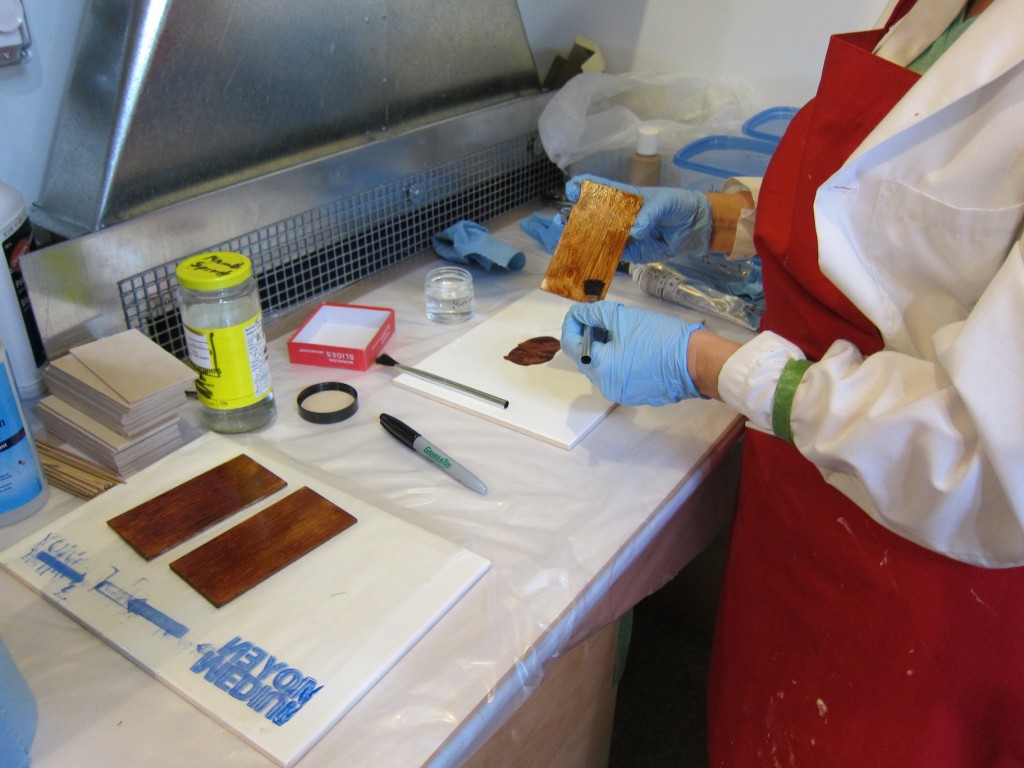

Fast forward 20 years to my first experience working with urushi. Although I used gloves and thought I was careful to keep it contained I still managed to get itching rough patches on my forearms. Many people have told me that if you persist in working with urushi you will develop immunity. I admit any rashes I have had since were mild, however, when I have been unprotected I have reacted. Perhaps it is the memories of the first exposure that makes me take the precautions that I do. Here are my tips for working with urushi.

Have a separate work area.

Have urushi work clothes, and keep them separate.

Wear gloves and change them frequently.

Use Ivy Block for unprotected areas of skin or under gloves.

Clean up urushi with solvents.

Dry all urushi tools, and trash such as cloths, gloves etc. before storage or disposal. I built two drying boxes for this reason, one for the boards and one for the trash.

Post warning signs for others.

Application of urushi to seal wood.

I was taught to use a mixture of kijiro and kijome, the Japanese terms for transparent processed lacquer and raw lacquer to seal the wood. I mixed them together in a ratio of 3:1 in a small glass bowl. It was brushed on using nylon disposable brushes from the dollar store to save time in cleaning. I allowed five to ten minutes for the urushi mixture to soak into the wood. When several areas had become dull I then applied a second coat. It was again allowed to penetrate the wood. Then the excess urushi was wiped off using a lint free cotton cloth. The surface was even and dull. The process was repeated on the second side. Because both sides need to dry I laid the boards on horizontal swab sticks to lift them off the shelf in the furo.